So you just finished designing that great neural network architecture of yours.

It has a blazing number of 300 fully connected layers interleaved with 200

convolutional

layers

with 20 channels each, where the result is fed as the seed of a glorious

bidirectional

stacked

LSTM with a pinch

of

attention.

After training you get an accuracy of 99.99%, and you’re ready to ship it to

production.

But then you realize the production constraints won’t allow you to run inference

using this beast. You need the inference to be done in under 200 milliseconds.

In other words, you need to chop off half of the layers, give up on using

convolutions, and let’s not get started about the costly LSTM…

If only you could make that amazing model faster!

Here at Taboola we did it. Well, not exactly… Let me explain.

One of our models has to predict CTR (Click Through Rate) of an item, or in

other words — the probability the user will like an article recommendation and

click on it.

The model has multiple modalities as input, each goes through a different

transformation. Some of them are:

- categorical features: these are

embedded

into a dense representation - image: the pixels are passed through convolutional and fully connected layers

- text: after being tokenized, the text is passed through a LSTM which is followed

by self attention

These processed modalities are then passed through fully connected layers in

order to learn the interactions between the modalities, and finally, they are

passed through a

MDN

layer.

As you can imagine, this model is slow.

We decided to insist on the predictive power of the model, instead of trimming

components, and came up with an engineering solution.

Let’s focus on the image component. The output of this component is a learned

representation of the image. In other words, given an image, the image component

outputs an embedding.

The model is deterministic, so given the same image will result with the same

embedding. This is costly, so we can cache it. Let me elaborate on how we

implemented it.

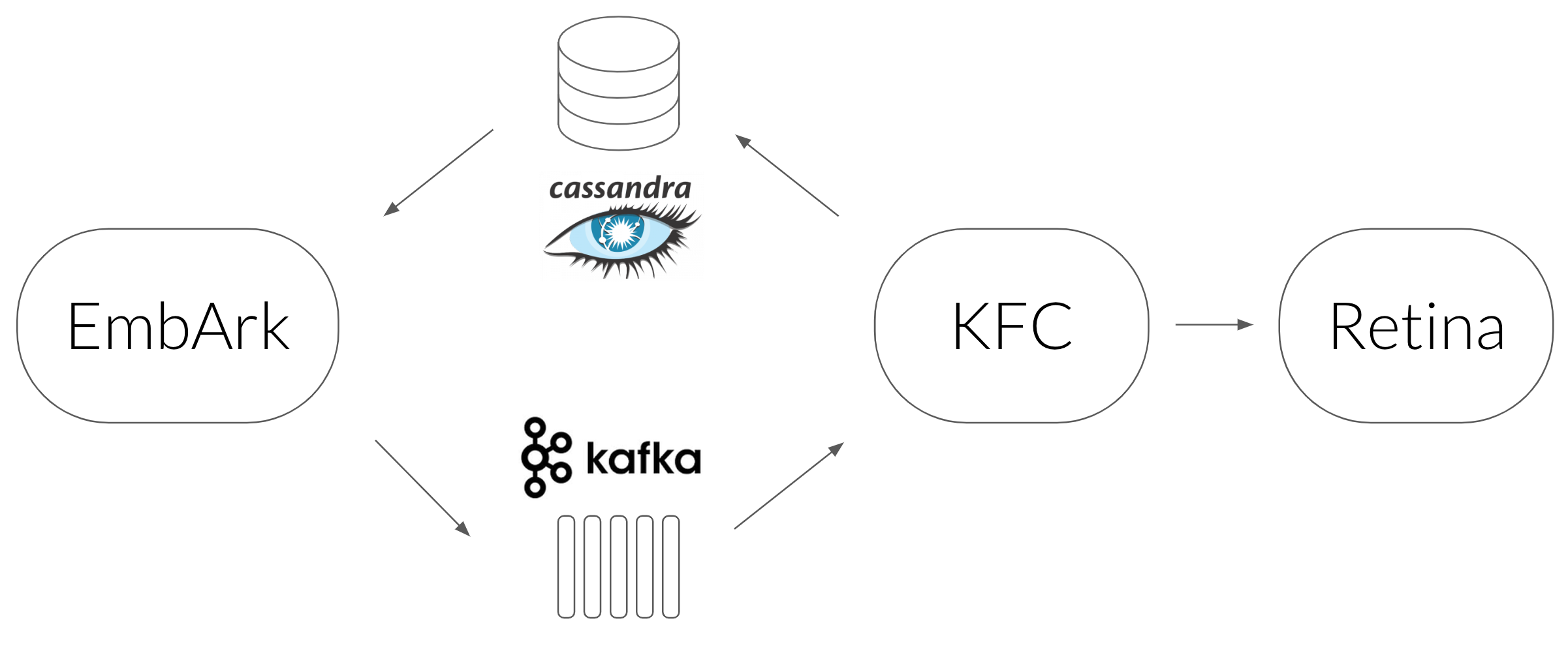

- We used a Cassandra database as the cache which

maps an image URL to its embedding. - The service which queries Cassandra is called EmbArk (Embedding Archive,

misspelled of

course).

It’s a gRPC server which gets an image URL from a client and

retrieves the embedding from Cassandra. On cache miss EmbArk sends an async

request to embed that image. Why async? Because we need EmbArk to respond with

the result as fast as it can. Given it can’t wait for the image to be embedded,

it returns a special OOV (Out Of Vocabulary) embedding. - The async mechanism we chose to use is Kafka — a

streaming platform used as a message queue. - The next link is KFC (Kafka Frontend Client) — a Kafka consumer we implemented

to pass messages synchronously to the embedding service, and save the resulting

embeddings in Cassandra. - The embedding service is called Retina. It gets an image URL from KFC, downloads

it, preprocesses it, and evaluates the convolutional layers to get the final

embedding. - The load balancing of all the components is done using

Linkerd. - EmbArk, KFC, Retina and Linkerd run inside Docker,

and they are orchestrated by Nomad. This allows

us to easily scale each component as we see fit.

This architecture was initially used for images. After proving its worth, we

decided to use it for other components as well, such as text.

EmbArk proved to be a nice solution for transfer

learning too. Let’s say we believe the content

of the image has a good signal for predicting CTR. Thus, a model trained for

classifying the object in an image such as

Inception

would be valuable for our needs. We can load Inception into Retina, tell the

model we intend to train that we want to use Inception embedding, and that’s it.

Not only that the inference time was improved, but also the training process.

This is possible only when we don’t want to train end to end, since gradients

can’t backpropagate through EmbArk.

So whenever you use a model in production you should use EmbArk, right? Well,

not always…

There are three pretty strict assumptions here.

1. OOV embedding for new inputs is not a big deal

It doesn’t hurt us that the first time we see an image we won’t have its

embedding.

In our production system it’s ok, since CTR is evaluated multiple times for the

same item during a short period of time. We create lists of items we want to

recommend every few minutes, so even if an item won’t make it into the list

because of non optimal CTR prediction, it will in the next cycle.

2. The rate of new inputs is low

It’s true that in Taboola we get lots of new items all the time. But relative to

the number of inferences we need to perform for already known items are not that

much.

3. Embeddings don’t change frequently

Since the embeddings are cached, we count on the fact they don’t change over

time. If they do, we’ll need to perform cache invalidation, and recalculate the

embeddings using Retina. If this would happen a lot we would lose the advantage

of the architecture. For cases such as inception or language modeling, this

assumption holds, since semantics don’t change significantly over time.

Sometimes using state of the art models can be problematic due to their

computational demands. By caching intermediate results (embeddings) we were able

to overcome this challenge, and still enjoy state of the art results.

This solution isn’t right for everyone, but if the three aforementioned

assumptions hold for your application, you could consider using a similar

architecture.

By using a microservices paradigm, other teams in the company were able to use

EmbArk for needs other than CTR prediction. One team for instance used EmbArk to

get image and text embeddings for detecting duplicates across different items.

But I’ll leave that story for another post…

Originally published by me at

engineering.taboola.com.

Credit to

Source by [author_name]

Review Website